Cláudio Assis

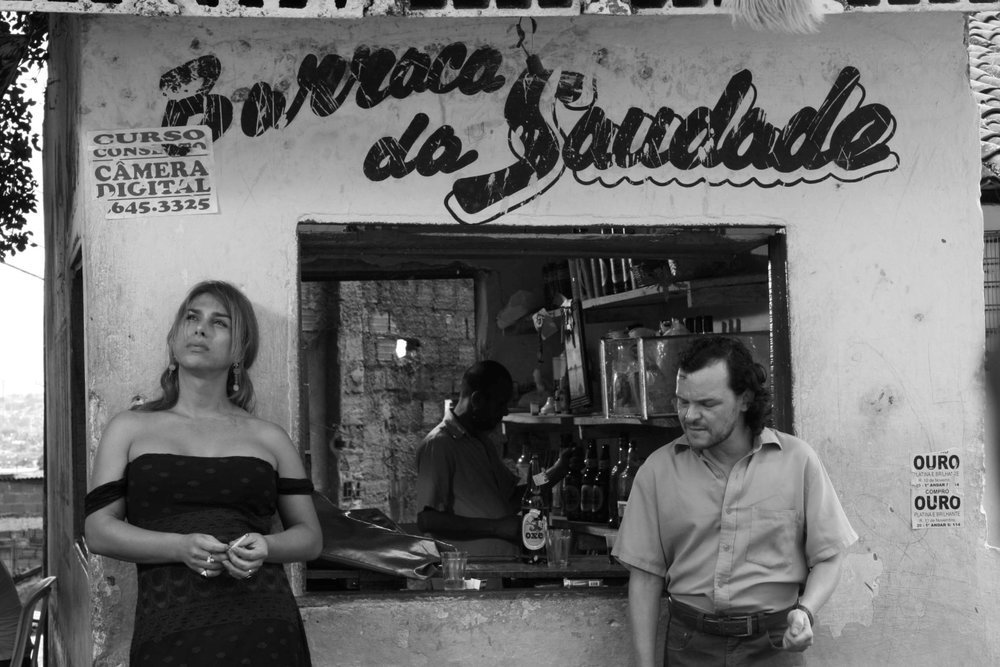

Rat Fever, Cláudio Assis (2011)

Cláudio Assis is a Brazilian screenwriter, producer and director. He was born in Caruaru, in the state of Pernambuco, and went to the state's capital Recife when he was 17 to study economics, but felt "totally incompatible" with its structure. He thus starting making films, first with Mango Yellow which won Best Film at Brasilia; his second film Bog of Beasts won the Tiger Award for Best Film at Rotterdam. Assis' third and fourth films, Rat Fever and Big Jato respectively, continue his examination of the power of poetry to shape society.

In an exclusive interview with Filmatique, Cláudio Assis discusses marginal poets of the 1970s, freedom, the failure of capitalism and his next project.

//

FILMATIQUE: Both Rat Fever and Big Jato embrace poetry as a method for subverting sociopolitical corruptions and the influence of capitalism, particularly in the slums of Brazil. Could you reflect on the dualism between bourgeois Brazilian life and existence in the slums of Recife? How does this dualism breed the particular artistic tones of Zizo and Xico, the poets in your films?

CLÁUDIO ASSIS: For me, these poets can be anything they want in life. Both Zizo and Xico can create the world they want. The poet is free. So when I wrote about Zizo, I wanted to make a homage to the marginal poets who used to exist in the 70s, and still do exist— there are still some of them today. So Zizo is alive.

Xico Sá is another person, he is also a writer, so we wanted to put this writer's voice in his mouth. What do I mean by that... it is what it is. Zizo is a representation of the marginal poetry nowadays.

FLMTQ: Instead of touching on expected issues such as labor, education, poverty, or health care system, the poet Zizo is awakened by radical hedonism. He seeks to liberate himself from the power systems that tame him linguistically and performatively, and dismantle a civil conscience that serves only to censor the pleasures of the senses. Zizo's anarchy thus drives toward the extreme realm of freedom— the freedom of sex, language, and other human conditions. What motivated the choice to have Zizo and Xico take this route, rather than address other urgent matters of living at the fringes of society?

CA: I think about both socialism and capitalism— even more capitalism, which is more bankrupt than socialism when it began. I don't have an ideology, but the ideology that I connect the most with is anarchism... it is Bakunin, it is Malatesta, and I think that the world is proving more and more that we are fucked, that there is no capitalism, because we are living in disgrace. Not only in Brazil, but all over the world. Capitalism is fated to failure; it is over.

So when we choose to talk about the route that Zizo and Xico take, it happens with a clear conscience. Freedom is the shape of sex, poetry, ways of intervention— ways to criticize the society in which they live, from the favelas to the city of Recife. These poets, they can do everything. They are anarchists and that is why they love, that is why they intervene in society.

In Big Jato, Xico can also do all things: he is an antagonist, he is two people in one. In this case Xico is inspired by the author of the novel, Xico Sá, representing the possibility to form the character of a child. The question then becomes, how is this child raised? This child is raised by two different people: one who is totally conservative, retrograde and the another who believes in poetry, who is the poet with his typewriter. It is two people in one, the father and the uncle become the same person, showing how you have to be careful with raising a child, with the child's character. The pursuit of poetry goes on this way with the hope to give freedom while raising a child, in order to create a better society.

Big Jato, Cláudio Assis (2015)