Kiarash Anvari

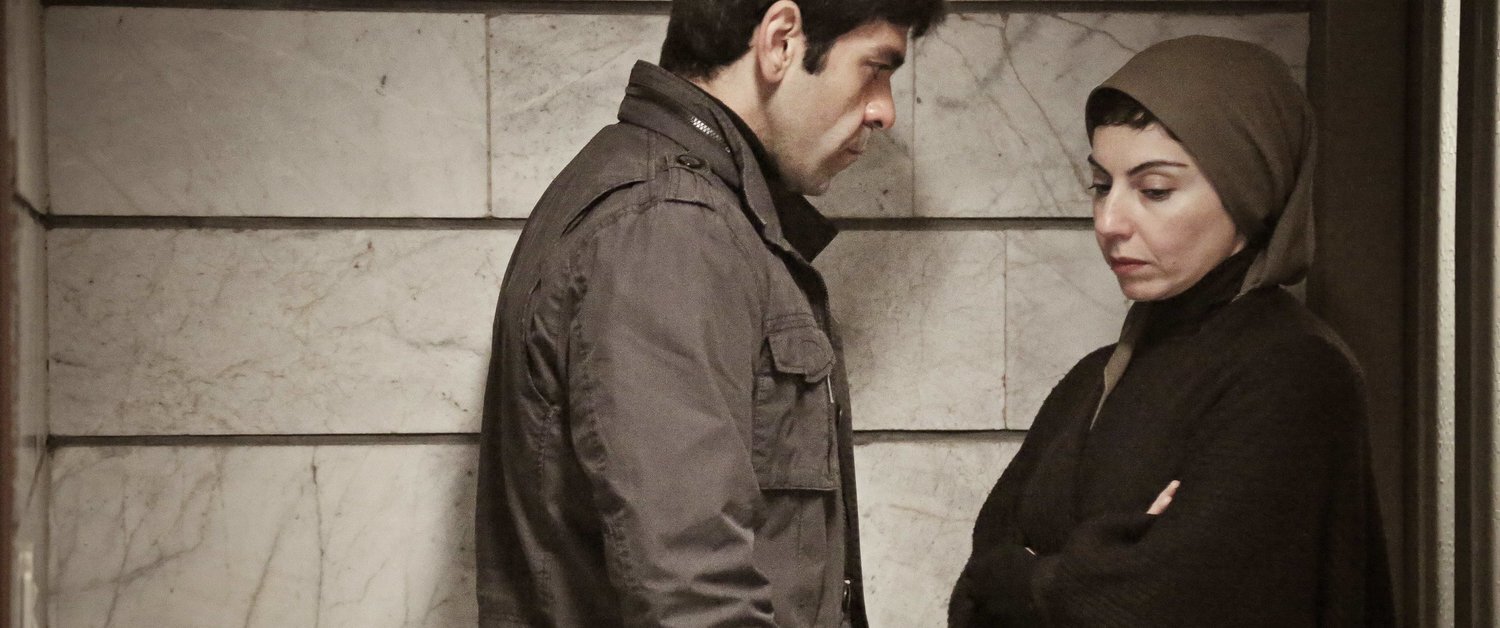

The Pot and the Oak , Kiarash Anvari (2017)

Kiarash Anvari is an Iranian film producer, screenwriter, editor and director. His short film Duet premiered at the Palm Springs Film Festival, Matsalu and Signes de Nuit; he also edited Ava, which premiered at Toronto where it won the FIPRESCI Prize and an Honorable Mention for Best Canadian First Feature Film. Anvari's feature debut The Pot and the Oak premiered at IFFR - Rotterdam International Film Festival, Jerusalem and Febiofest Prague.

In an exclusive interview with Filmatique, Kiarash Anvari discusses hypermasculinity in Iranian society, abstraction and enstrangement, creativity amidst obstacles and his next project.

//

FILMATIQUE: The Pot and the Oak traces the rapid unraveling of Borzoo, a middle-aged Iranian man, when he discovers that he is impotent. While the circumstances of his life— the deterioration of his marriage, his declining career— are tragic, the film is interspersed with moments of dry humor. What was your inspiration for this film?

KA: In my opinion, the tragedy is not that Borzoo is impotent, that his marriage is deteriorating or that his career is declining. The issue is deeper: he's not in a fit state to adapt himself with the reality around him. He's not able to face it. In other words, he doesn't have the capacity to accept the truth, just as a small pot doesn't have the capacity to hold a huge tree. In this sense, he sees himself as Hamlet—but unlike Hamlet, he has no charm. He is neither beautiful nor subtle, neither a poet nor a philosopher. He's neither romantic nor young like Hamlet. He doesn't express his feelings, but that doesn't make him an introvert or a tactful person. He simply doesn't know how to express himself. That's why every time he decides to emancipate his feelings he does it in the wrong way.

If I want to describe his character in a sentence, for example, I can say that he’s the intellectual model of Travis Bickle. In fact, the humor of this film comes from this contradiction within Borzoo's character. For me, he's like Lucian Freud's portraits. From the facial expressions of people in Freud's paintings—the exaggerated wrinkles on their faces, the form of their eyes and gazes—one can perceive their uneasy souls, their loneliness, their psychic wounds, their mental and physical disabilities. But at the same time, these characteristics give these paintings a form of a caricature. Tragedy results from contradiction: the combination of a human being's suffering and inner complexes with distorted comic attitudes and appearances.

FLMTQ: Borzoo's inability to have children mirrors and perhaps contributes to his failures across other arenas of life. Meanwhile Hilda, his wife is steadfast and strong in her decisions. To what extent do you believe Borzoo's impotence allegorizes a certain generation of Iranian men? Were you seeking to draw a portrait of masculinity in contemporary Iran, or simply one of an artist in existential peril?

KA: The place where an individual lives and grows is a part of his/her being and has a deep connection with his/her mental and emotional state. Therefore, Borzoo's hypermasculinity complex is the result of the community in which he grew up. This is not just Borzoo’s story, but the story of all men who have been raised in such circumstances. As an Iranian, I've also grown up in a society in which manhood and masculinity are always deemed superior. During all these years, and due to some fortunate social changes, I saw the gradual disappearance of this supremacy. Nevertheless, there are still those who do not accept these social changes and resist these developments.

The film is about them. It's an allegory of the gradual disappearance of patriarchal thinking and the shaky situation of masculinity in Iranian society. Many films have been made on the status of Iranian women and how much they struggle with the patriarchal community around them. As far as I'm aware, never before was a movie made to look at the gender conflicts in Iranian society from another angle. However, I didn't want to judge the situation. I just wanted to observe and let the viewers judge. I wanted to let this situation gradually unfold in front of the viewers' eyes. Because I believe if you want to make something worthless, first let it expand. If you want to get rid of something, first let it flourish. This is a subtle understanding of the law of being. And, as Bresson says, "Truth must not be sought in events, people, and things, but one must find it in the emotion that all of these exclaim."

The Pot and the Oak, Kiarash Anvari (2017)