Miko Revereza

No Data Plan, Miko Revereza (2019)

Miko Revereza is a film director, producer, editor and sound designer based in the United States. Spanning short films, gallery installations and music videos, Revereza's body of work examines the process of documenting the undocumented; he himself has lived in the United States undocumented for over 20 years and does not conceal this fact. Revereza's short film Disintegration 93—96 screened at Rotterdam last year; likewise he was named among Filmmaker Magazine's 25 New Faces of Independent Film 2018.

A lyrical portrait of the precariousness of undocumented existence, Revereza's debut feature No Data Plan screened its world premiere at the 2019 edition of IFFR - International Film Festival Rotterdam. In an exclusive interview with Filmatique, Revereza discusses opening imaginative spaces in film, the politics of private prisons, an American future devoid of hope and the necessity of stateless peoples telling their own stories.

//

FILMATIQUE: Unfolding almost entirely within the confines of an Amtrak traveling from Los Angeles to New York, No Data Plan is a powerful testimony of the fragile and precarious existence of those not legally in the United States. When did you decide to tell this story, and when did the project inherit new urgency for you as a filmmaker?

MIKO REVEREZA: This trip was the second time I took the train across the country. I tried to shoot the first time but I had too many hesitations. This time however, I didn't even think about whether I was shooting or not. I did not expect to make a film. I just had to get across the country. They didn't have WiFi on the train and since I have "no data plan" on my phone, I had nothing better to do than to sit with my thoughts and observe my surroundings.

There was no urgency to tell a story, if anything, it was my lack of urgency to do anything that made it a meditational piece. The stasis and boredom of being confined to a train for 3 days allows for thoughts to run wild. The sound of the train and inability to get a full night's sleep gave me weird dreams. I'll admit that most of the time, I thought I was just collecting footage for fun. It wasn't until the last moments when I had a close encounter with Border Patrol that it became too real. That's when the reality of my precarious travel struck me and I was facing the moment of my potential detainment.

After it passed, I was so angry, so full of rage in my heart. My hands were shaking uncontrollably and I could not shoot straight. Yet, that shakiness was the only camera movement that made sense in the moment. That was the most significant shot I've ever taken because within it, I am witnessing my cinematography break down as I realize the inseparability between my moving image and my moving body.

No Data Plan, Miko Revereza (2019)

FLMTQ: The film poignantly juxtaposes sound and image, overlaying spoken anecdotes on quotidian images of this journey— vast open plains, the outskirts of cities, abandoned industrial sites, commercial parking lots— evoking a physical and psychological landscape most Americans will never know. The film's unspoken subtitles add an additional layer of meaning. How did you conceive of this particular filmic structure?

MR: As for the unspoken subtitles, I struggled a lot with if they should be spoken in actual voice over. Every time, there was such a big clash between the recorded voice competing with the industrial soundscape of the train. In the end, I prioritized the soundscape of the train. I believe that the subtitles with no voice enables the viewer to hear it in their own voice. To experience their own internal monologue in the theatre like I did on the train. My thoughts were silent but loud in my head. Since they are subtitles, I imagined the absent voice would speak in a non-English language and I imagined viewers of different diasporas inserting their own mental voice and language into the film.

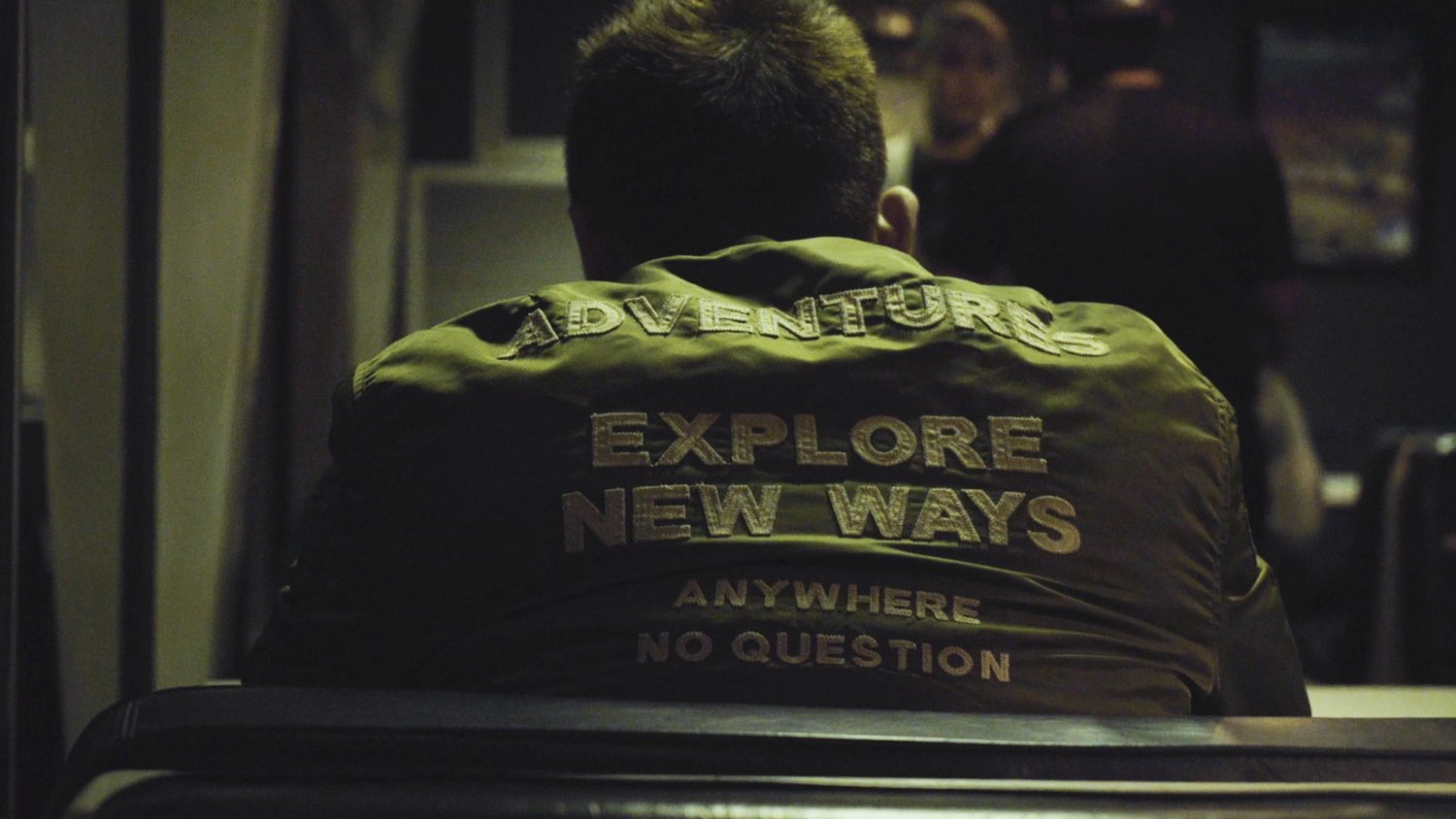

FLMTQ: For obvious reasons, the film never directly reveals the characters' faces, underscoring the anonymity of those forced to live unrecognized in any legal or judicial sense. Other passengers on the train are similarly framed from behind, or backlit, our vision of them obscured. Within this liminal state of collective identity, what hope do you see for a country grappling its way toward an unknown future?

MR: After this experience on the train, I honestly have very little hope for the USA. It was a huge turning point for me and at the end of this journey I was resolved that my only way forward is to leave. As long as there are private prison corporations turning a profit, there will be mass immigration detainment. As long as affiliated corporations are dependent on cheap goods produced by prison labor, and as long as politicians are beholden to the interests of private prison corporations, there will be no significant change on a broken immigration system. It is broken for us so-called Dreamers but it is big business for private prisons and their stock holders. If you want to abolish ICE, abolish private prisons.

That said, I have lived here long enough. After 26 years with still no path towards legal residency, I just don't see my future here anymore. I've missed so many opportunities to travel with my films because of my perpetual stasis here. That is what the US symbolizes to me: to be stuck in a stasis, stuck in a bureaucratic maze, stuck in bygone delusions of a 90's American dream. That shit is dead to me.

No Data Plan, Miko Revereza (2019)

FLMTQ: There is a certain poetic irony in the task of documenting the undocumented. Given your history of exclusion, what has been the most painful and/or rewarding aspect of your experience as a filmmaker?

MR: The most painful aspect of filmmaking is living itself and taking the time to analyze how I am living and what I am thinking about. It's also painful telling my story and my family's story and to play back the moments of trauma over and over in the editing process. It's complicated and risky being a visible undocumented documentary filmmaker but I hope that more undocumented and stateless voices will step forward and tell their own stories in their own uncompromising vision. Because if we don't, our stories will be extracted, edited and commodified for us by "socially conscious" documentary filmmakers flattening our experiences into a singular social issue. We have to make better films than these grant-hogging assholes banking on our sad situations, since as stateless people we're often excluded from the eligibility of these grants.

The most rewarding aspect of filmmaking for me is finding the poetry in mundane moments. Finding the feeling in how things move and how light touches surfaces. That's when they cease to be boring. I am rewarded by being conscious of a fleeting moment and being there to observe something in front of me, whether I have a camera on me or not.

FLMTQ: Are you working on any new projects, and if so, can you tell us a bit about them?

MR: I am working on my exit plan and what kind of film will come out of this exile from the United States. I can speculate but really have no idea until I embark on that next journey.

No Data Plan, Miko Revereza (2019)